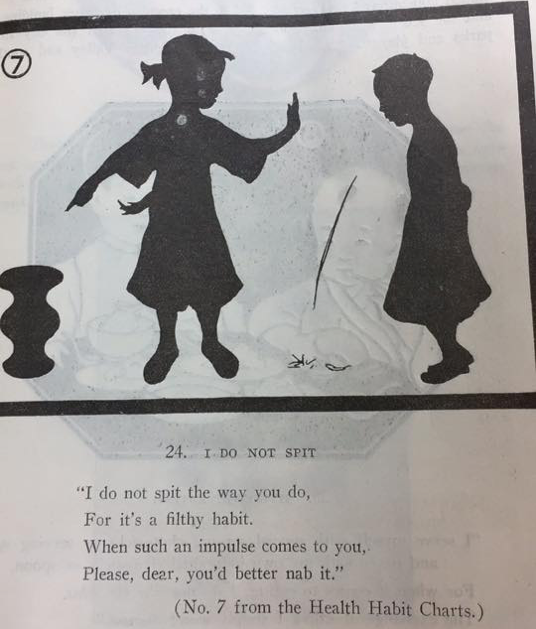

I had the privilege of finding out earlier this month that I won a graduate student prize from the Association of Asian Studies for a paper I presented last year on the prohibition of spitting in the Shanghai International Settlement. Among my primary sources were the juiciest, LOL-worthy commentaries and letters to the editor in some of Shanghai’s newspapers from the 1910s to the 1940s. The writers, often under pseudonyms, bickered among themselves about the best ways to eliminate spit from the sidewalks of their cosmopolitan city (which was conveniently only made possible by its reliance on low cost Chinese coolie labour). The foreign residents in Shanghai had money, land, and a truly functional democratic process, but they were frustrated that they could not exercise their autonomy over the cleanliness of their city streets. Very little — legally — was done to really stem the phlegmy flows during this time, but the public, especially those who had the unfortunate experience of having been spat on, sure liked to talk about it.

Perhaps the esteemed Association felt that the various pieces of advice and complaints, given by all manner of Shanghai residents to the government, the press, and each other, were on point and timely. Spit still remains a problem in the 21st century, and very few governments seem capable of actually enforcing a thorough ban. Is it time for the public to take charge?

If you’re dealing with an epidemic of phlegm coating your city sidewalks, perhaps you may want to take a look at some of these suggestions, helpfully separated by theme. See if you can find the possible racial slur. [all emphasis mine]

GROSS COMMUTERS CAN GTFO

“Another point… is spitting in the tramcars. This objectionable habit, evil in its effects, is far too common. It is not confined to the Chinese; Europeans are also guilty. Whether first or third class, no distinction is made. Chinese, of course, are the worst offenders, and nothing seems to check them. The conductor ought to be empowered to eject any passenger from a car who is guilty of expectorating. It would be far more effective than a thousand notices prohibiting spitting.” — “Spread of Disease” June 2 1915:

“I have been on the unfortunate just outside no less than three times, the last time on the Bund at 8.55 this morning, and it seems a pity that such unhygienic and disgusting practices should pass without a protest. The notice “no spitting allowed” refers to not only inside but out of the trams. If this rule were more vigorously enforced, and some punishment, say “chucking out” the offender were imposed and insisted upon, surely there lies at hand a simple and effective remedy. It is sad to observe that not only our Chinese friends are guilty of this breach of matters. Foreigners also should refrain. Though careful, we cannot expect the Chinese to comply with the rules that we do not observe.” — Usque ad Nauseum, “A Nasty Habit”, September 22, 1917

DO WE TEACH THEM, FINE THEM, OR REDIRECT THEM?

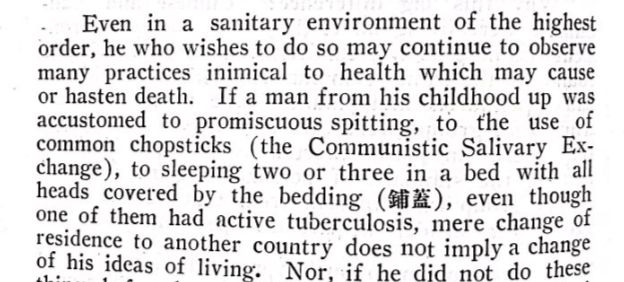

“It is a question of education rather than legislation. There are countries where the spitting habits worse than in China. Right in Shanghai, great progress has been made during the last 10 years. Thousands of visitors to this city can bear testimony tot he fact that spitting is scarcely seen in hotels and big store here.” — Dr. Wu Lien-teh, June 7, 1933.

“Peoples of the outer world may not at first be able to understand the necessity for such a movement but they will do so when they realize that it is to correct old evils that Gen. Chiang is now taking action along a psychological and educational line.” — “Various phases of ‘New Life'”, December 20, 1934.

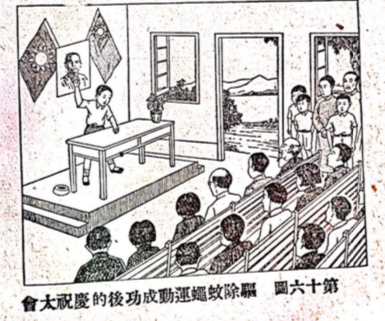

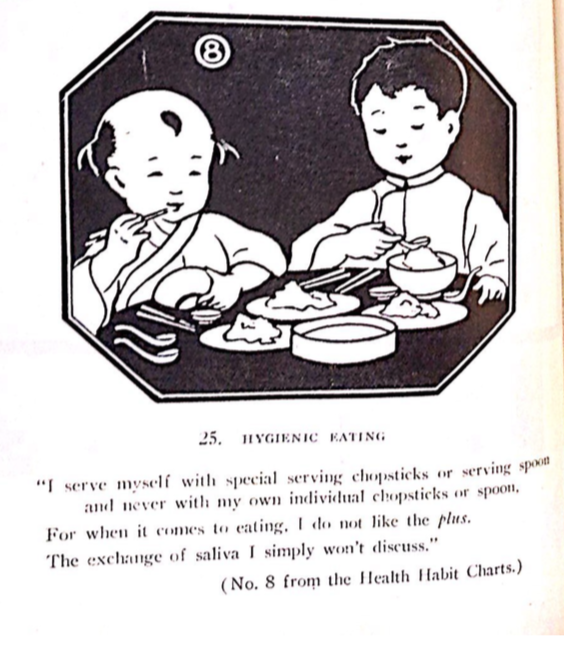

“A two-week exhibition… under the auspices of the Anti-Tuberculosis Association of China. The musical program included choral singing of the “Anti-TB” Song”, which brings home the message that anti-tuberculosis activities should not overlook the danger to the public of spitting in improper places, and stresses the fact that a strong nation requires a strong and healthy people.” — October 6, 1935.

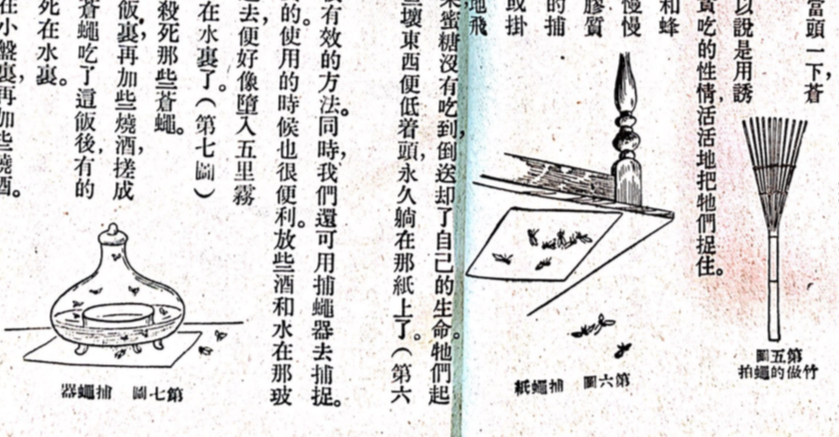

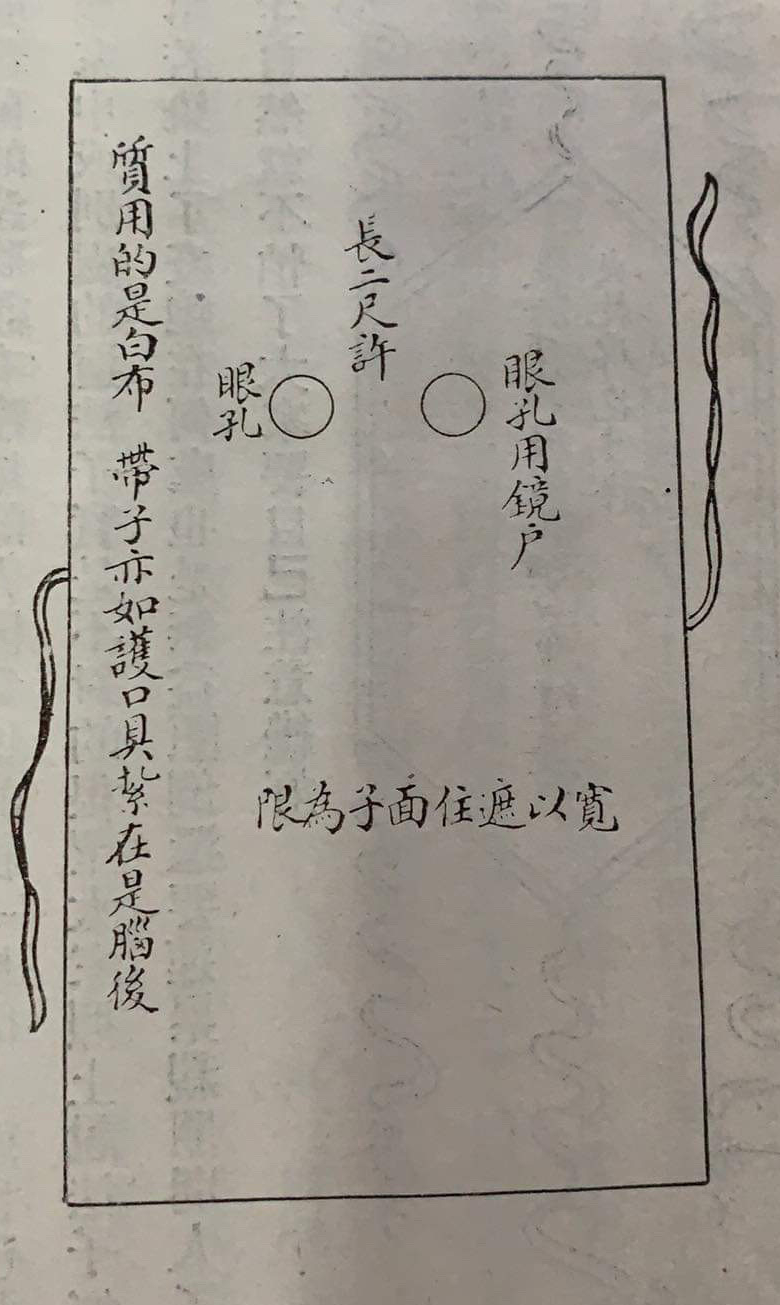

“… while foreigners are apt to regard spitting itself as objectionable on aesthetic grounds, the truth is that where a race is subject to nasal or other catarrh, spitting into a suitable receptacle [spittoons] makes the act as clean a practice as that followed by those who do not spit. This is the severely scientific attitude towards the subject and it does not, of course, take into account the feelings of those who find spitting objectionable to the ear as well as to the other senses.” February 26, 1936.

“Perhaps [the previous letter writer] is actually suffering from the August heat, or is he just a little squint-eyed? In my previous letter re the subject of spitting I suggested that the [Shanghai Municipal Police] collect 20 cents from offenders as a penalty for spitting on pavements, and I still believe this would be a lucrative source of revenue…” August 24, 1938.

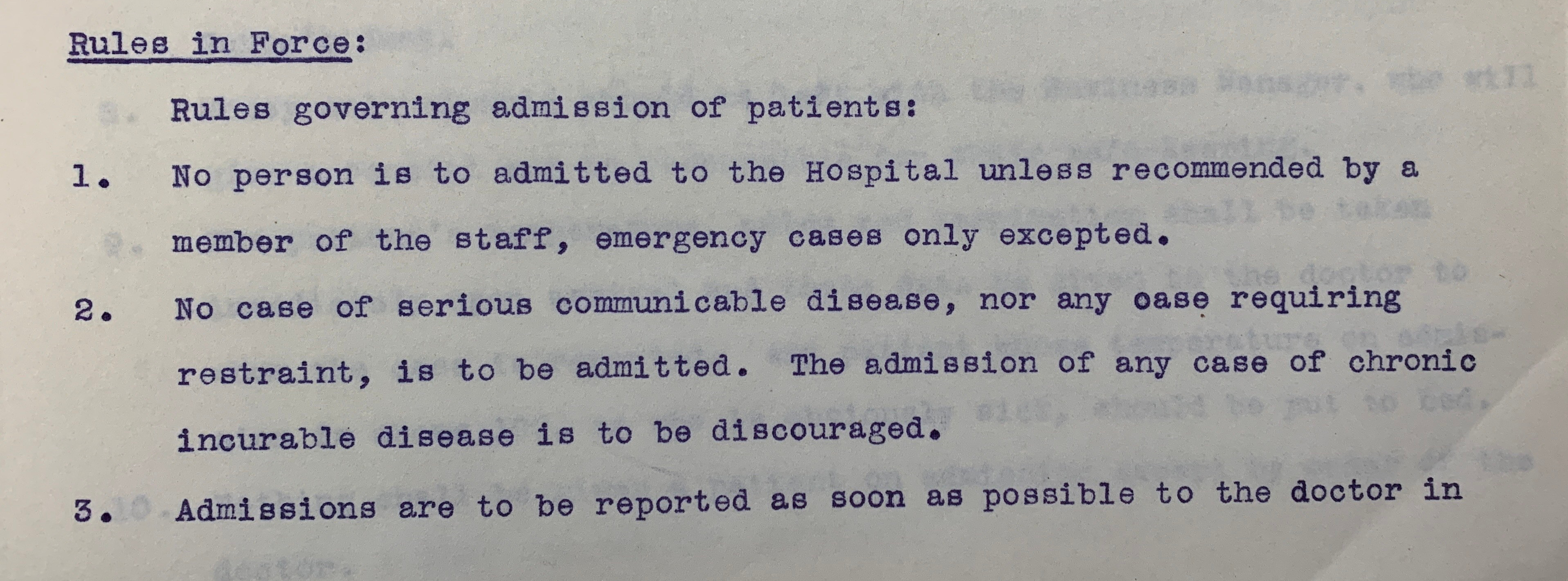

“It is realised that the enforcement of the spitting Bye-law will be difficult… public enlightenment as to the unhealthiness of this habit through health campaigns will continue. The introduction of a Bye-law for application in cases where the necessity arises is most desirable.” — April 9, 1941.

CAN/WILL THE CHINESE LEARN?

“I think that this spitting is scandalous too; but I regret the moderation of your correspondent ‘Resident.’ I would go a step further and deprive the Chinese of the right to breathe on The Bund or anywhere else where I am near for the aroma of garlic discharged by some of them, not only through wide nostrils but also through open capacious mouths, is becoming insufferable.” December 14, 1914.

“Apparently it is not against Chinese etiquette to make these horrible noises and to spit indoors, but in the interests of public health it is time they learnt differently.

If, instead of a campaign against men and women walking together in the streets, the Chinese authorities were to concentrate on attacking the spitting habit, some good might be done. No wonder consumption is rife in China, with everyone spitting all day long.” — July 20, 1934

“It is said that native upbringing is either literally or traditionally based on the Confucian Canon, but I doubt if it advocates full and hearty expectoration in public. Yet a common sight in Chinese restaurants, hotels, etc., is an abundance of spittoons for the customer’s convenience.” — June 1, 1938.

“The collection of a 20 cent fine on the spot is hardly a difficult matter, as my understanding of the Chinese is he would rather stump up on demand than to “lose face” by having a very curious crowd of fellow-countrymen gazing upon him.” August 31, 1938.

IT’S BETTER IN THAN OUT, REALLY!

“Outside of the fact that it is a dangerous disease spreader, spitting on floors, on streets, or in other public places wastes a very useful secretion of the human body.

Therefore, for your own health’s sake, don’t spit. Don’t lick postage stamps if there is any other way of moistening them. And don’t moisten your thumb to turn the leaves of pages or to count paper money.” — Dr Morris Fishbein, “Save Your Saliva”, February 26, 1934.

A FINAL WORD FROM THE (WANNABE) SPITTERS

“I often think that if Chinese people spit, it may be because we have no other way to air our grievances. I myself want to swear loudly and lob a mouthful of spit every time I think about how Chinese people have suffered under foreign invasions and from internal aggression. But in America, where [ironically] this freedom does not exist, I can only write an essay to vent.” — C. Y. LEE, 1947.